Every day, Volodymyr Zatulyviter descends 600 meters into one of Ukraine’s three remaining uranium mines, knowing he might not even get paid for it.

The 26-year-old miner from Smoline village of Kirovohrad Oblast and others like him keep Ukraine’s lights on.

The Smolinska mine, where Zatulyviter works, supplies uranium concentrate to Energoatom, Ukraine’s state nuclear power company, which makes more than half of the country’s electricity. Close to another third of the country’s power comes from burning coal, produced from dozens of coal mines around the country.

Despite the importance and danger of his job, Zatulyviter often goes without pay. On June 14, he and dozens of colleagues traveled 300 kilometers to Kyiv to protest.

“This has been going on for two years. We do our jobs, breathing toxic air and working in the contaminated water of the mine, wearing our old gear. And then we also have to protest to get our salaries,” Zatulyviter said.

“After they paid us, they had no money left for the mines to keep working. Either we get our money and the mine stops, or we keep it alive but work for free.”

The Smolinska Mine has been on the verge of collapse for two years. The heads of the Skhid GZK company, which runs all three uranium mines in the region, accuse Energoatom of not paying for the uranium on time, saying it owes the mines Hr 600 million ($21.8 million).

But Energoatom claims its payments are timely, like the Hr 200 million ($7.2 million) payment it made on June 15, right after a miners’ protest in Kyiv.

But the problem is bigger than any one company. Miners say the entire industry that employs 70,000 people is broken.

“Our gear is old and crappy. Our equipment hasn’t been repaired for years. Meanwhile, our chiefs get huge salaries. For what?” Zatulyviter said.

In 2020, the Skhid GZK mining company lost Hr 550 million ($20 million). However, its acting head, Anton Bendyk, was paid a salary of more than Hr 1 million ($36,000) for the year. Skhid GZK’s press service did not respond to a request for comment.

Mykhailo Volynets, chief of the Free Trade Unions Confederation of Ukraine, said that most state-owned mines share the same story of corruption and mismanagement. Even when mining companies post huge losses and rack up debts, their directors continue to enjoy high salaries at everyone else’s expense.

The bosses spend peanuts on maintenance, leading to more financial losses.

As the mines age and crumble, Ukraine relies more and more on coal imports, including from its invader, Russia.

Out of order

In 2014, some 121 coal mines were operating in Ukraine, according to the government. By 2021, Ukraine controlled only 33 of them.

The state lost control of more than 80 mines after Russia invaded Ukraine, seized large parts of the Donbas and killed nearly 14,000 people.

But the mines that remained under Ukraine’s control are barely surviving.

“Some mines are out of action for 6–8 months at a time, their electricity is cut off for unpaid debts,” Volynets told the Kyiv Post. “Only the air conditioning and water pumping systems work. And people still have to be paid even if a mine doesn’t extract anything.”

Many mines are deeply unprofitable and rely on subsidies to survive.

“The government throws billions at the industry but people still have to strike to get their salaries,” Volynets said.

Over 70,000 Ukrainians are currently employed by the mines, according to the Free Trade Unions Confederation. They include miners, mechanics, cleaning, and technical staff.

In many areas, mines are the only employers in town, keeping their economically depressed regions on life support. Most of them are in eastern Ukraine, close to the front line held by Russia-backed militants.

Miners prepare for a descending into the D.F Melnikov Mine in Lysychansk, a city in Luhansk Oblast on Jan. 31, 2017. (UNIAN)

Struggling to survive

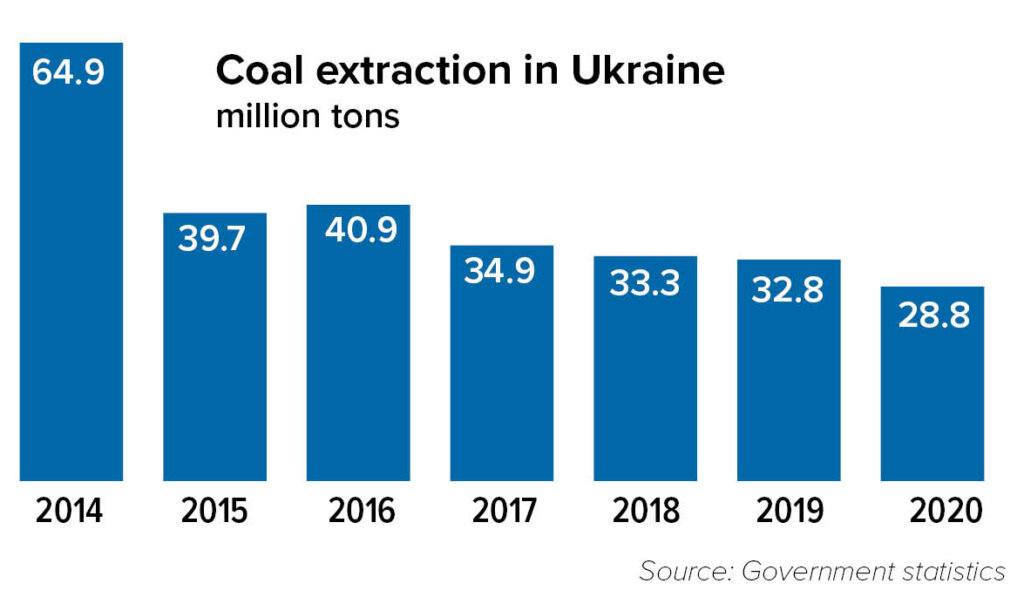

Coal production in Ukraine dropped from 64.9 million tons in 2014 to 28.8 million tons in 2020.

“State-owned mines produced 2.6 million tons in 2020, 2.2 million tons of which were energy coal. For comparison, in 2015 state mines produced 6.7 million tons,” Olga Buslavets, former acting energy minister of Ukraine told the Kyiv Post.

Worse yet, every year, getting coal out of the ground becomes more expensive.

“The production cost of Ukrainian coal increased by 80% in the last five years,” Buslavets said.

In 2020, it cost Hr 3,833 ($139) to extract a ton of coal, which then sold for Hr 1,451 ($52), meaning mines were losing money on each ton.

“The state had to invest more and more into the state mining companies every year. State subsidies grew from Hr 1.2 billion ($43.6 million) in 2015 to Hr 5 billion ($181.8 million) in 2020,” Buslavets said.

Between 2015–2020 the mining companies’ debts to the state grew to Hr 32 billion ($1.1 billion).

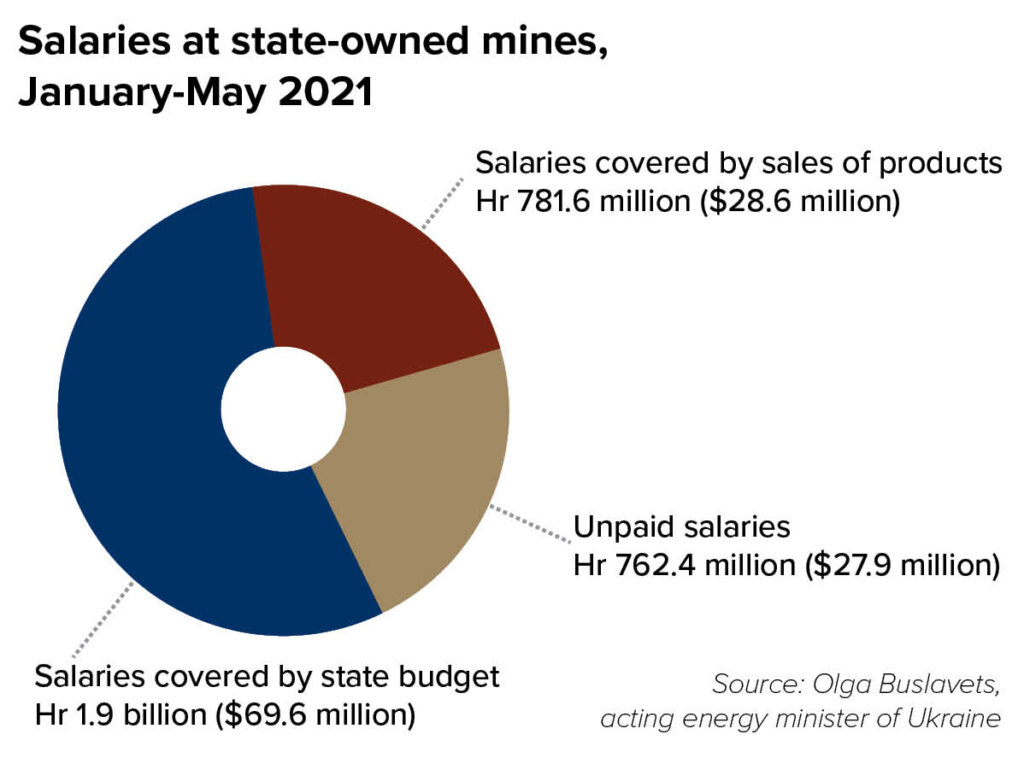

Their debts to employees also ballooned. In 2016, mines used coal revenue to cover 70% of their salary costs while the government paid for the rest. In 2020, mines could cover only 25% of salaries, according to Buslavets.

Coal production in Ukraine has plummeted since 2014. Russia seized most of the mines in Donbas and the rest have been slowly falling apart due to shrinking profitability, lack of maintenance and Ukraine’s deeply problematic energy system.

Huge debts

As of June 2021, the Ukrainian government owed more than Hr 367.5 million ($13.3 million) in unpaid salaries to miners, accrued between 2015–2020, as well as Hr 752 million ($27.3 million) accrued in the first five months of 2021, Ukraine’s Coal and Energy Ministry press service told the Kyiv Post.

As a result, miners occasionally have to protest or hunger strike to get their salaries.

“Many of them got their utilities at homes shut off, as they don’t have the money to pay for electricity, heating, and hot water,” Volynets said.

In 2016, Viktor Trifonov, a 60-year-old former miner and the head of the Miners Trade Union of Selidove, a town in Donetsk Oblast, set himself on fire in front of the Energy Ministry in Kyiv. He survived.

“I did that because people expected I could help them to get their money. Our hunger strike didn’t work. I was desperate,” Trifonov said. The ministry soon covered its debts at the time.

Protests for salaries have become part of Ukrainian miners’ work culture.

As a result, many of the miners the Kyiv Post talked to near the Energy Ministry fell for the militants’ propaganda that the miners were honored in the USSR and have to beg for their salaries in Ukraine.

Following several protests, on July 14, the Cabinet of Ministers ruled to pay Hr 393 million in salary debts to state-employed miners.

In recent years, state-owned mines have become less and less profitable. Employee salaries were once covered by the mine’s income but now they depend heavily on government subsidies and miners often go without pay.

Fear of the future

Ukraine produced up to 30% of its energy from coal in 2020, with domestic coal accounting for 27%. The remaining few percent comes from other sources, including imports from the EU, Russia, and Belarus.

The importance of coal in Ukraine’s energy sector falls every year, as the government turns to renewable energy.

Under the decarbonization plan, announced in Ukraine in recent years, authorities plan to close most state coal mines by 2030, which is a terrifying proposition for miners.

They believe that this program is a convenient cover for Ukrainian authorities who want to bankrupt and close the mines keeping dozens of industrial towns alive in eastern Ukraine.

The closures could be very costly for Ukraine, Volynets said.

Energy and security

Most of Ukraine’s mines are outdated and haven’t been properly maintained for dozens of years due to a lack of financing.

But simply closing them is not really an option. For one, without its own coal production, Ukraine may become even more dependent on Russia.

“If the government destroys the whole mining industry, that will put Ukraine’s energy and thus national security in danger,” Volynets said.

Worse, if the government closes down the mines without providing alternative jobs to the locals, they could turn against Ukraine. Most of the mines are near the war front and mine closures could stoke separatism, Volynets said.

Toretsk, a city of 60,000 people in Donetsk Oblast, still remembers the shutdowns of electricity during the hottest phase of the war in 2014. The pro-Russian militants were only driven out of the city by the summer of that year.

But many residents are still unsure which side to support, local activist Volodymyr Yelets said. The city is full of retirees, while people of working age are employed by two coal mines and a phenol plant. If the mines are closed, more than 2,000 people will lose their jobs.

“They should provide us an alternative first, not just shut down the mines. If the mines die, the city would die too,” said Dmytro Bondar, a 26-year-old miner from Toretsk.

Yet Vasyl Chynchyk, the head of Toretsk city administration, said businesses are in no hurry to invest in a region that can be occupied if the Donbas war heats up. The occupied town of Horlivka, one of the Russia-backed militants’ strongholds, is just eight kilometers east of Toretsk.

“If the Ukrainian government hires more professional people to control the state mining companies and invests into modernization it would even show people from the occupied Donbas mining regions that there’s light at the end of the tunnel here,” Volynets said.

Falling production suggests that there is not much light to speak of.

Solution

As coal production falls, Ukraine imports more every year, from the United States, Kazakhstan and Russia.

Buslavets said that Ukraine has been buying mostly anthracite coal, as most of its own anthracite mines are currently under Russian occupation. In 2020, Ukraine imported 2.6 million tons of coal for energy needs, 2.4 million tons were from Russia, 137,000 tons from the U.S, and 53,000 tons from Kazakhstan.

However, the situation can still be improved. Modernizing state coal mines could raise domestic production to 12 million tons per year, Ukraine’s Energy Ministry press service told the Kyiv Post.

“We can achieve this with the modernization of our mines in the next 3–6 years. The modernization could save $1 billion and fully cover the internal demand and the energy security of the state,” the ministry said.

The increasing number of extraction will be the main factor for the decreasing of its valued price and better quality.

The shortage of money for modernization keeps this revival from happening. In 2021, the energy ministry asked the government to invest Hr 6.7 billion ($243 million) for this project. Before that during 2013–2017 and 2020–2021 mines got no maintenance funds, the ministry said.

In 2018, the mining companies got Hr 307 million ($11 million), just 12 percent of what it needed for modernization. And in 2019 the mines got just Hr 397 million ($14.4 million) out of the Hr 2.5 billion ($90 million) they needed.

How to solve the crisis?

The outdated and corrupt mining industry is just one of Ukraine’s energy challenges. It seems that Ukraine’s energy industry is in perpetual crisis.

Buslavets blamed poorly regulated energy prices that do not cover production value.

In the summer, renewables cover Ukraine’s electricity needs, while the heating stations work at minimum capacity and can’t earn enough money to modernize or afford enough coal to cover the winter season, Buslavets added.

In summer, Ukraine has more than enough electricity but the government still heavily relies on electricity imports from Russia in autumn and winter.

This can potentially squeeze Ukrainian energy producers out of the market, as they may not have enough money to buy enough coal and gas for the heating season.

Ukraine sees only one way out of this crisis — synchronizing its energy system with the European Union system ENTSO-E.

The first testing of the new connection is planned for the fall and winter of 2021–2022, when Ukraine connects its energy system with Moldova.

However, the new energy system will work in the future. At present, the only way to prepare for a heating season is to repair as much mines and power plants as possible and stock up on as much gas and coal as possible.

The same approach allowed Ukraine to survive winter 2020–2021 without blackouts.

Part of the reporting for this story was done for NBC News Universal.