Editor’s Note: People mentioned in this article live in Russian-occupied Donetsk or have relatives living under occupation. Donetsk, a city with a pre-war population of 1 million people located 750 kilometers southeast of Kyiv, is now controlled by militants under Russian command. Human rights abuses including kidnappings, illegal detention and torture are well documented. To protect the people sharing sensitive information, the Kyiv Post is not publishing their surnames.

In early August, Darya found out that her grandmother, who raised her from birth, had died. Darya’s first thought was to rush to the western Ukrainian city of Lviv to say one final goodbye.

But she couldn’t. Darya lives in Donetsk, a city in eastern Ukraine that has been occupied by Russian separatist forces since 2014.

Before the war, the 1,000 kilometers from Donetsk to Lviv equaled a 15-hour train trip. Now, they might as well be on different continents.

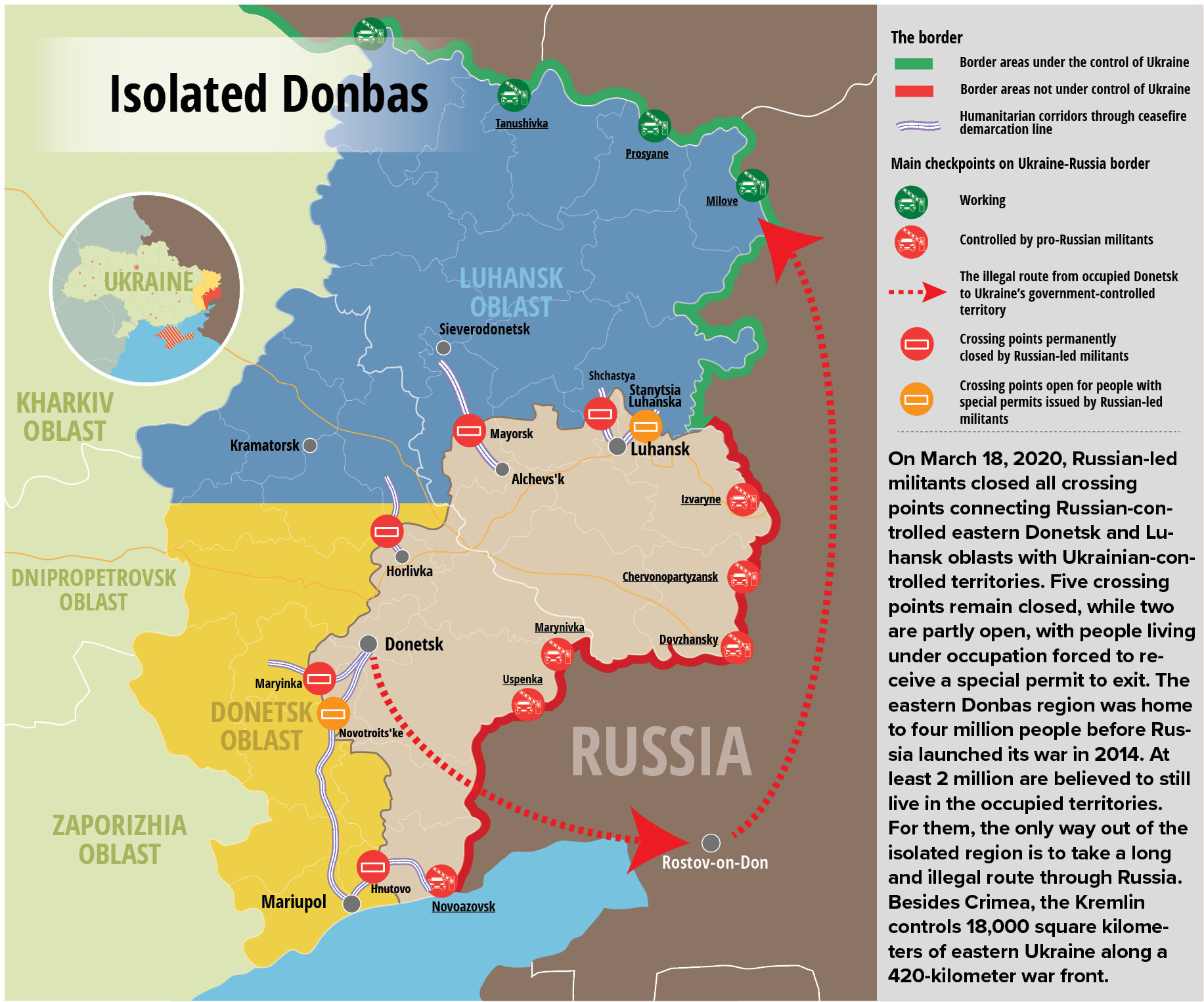

Since March, Russia has de facto closed all crossing points between the occupied eastern Donbas and the Ukrainian government-controlled territory.

“I (officially) have the right to freedom of movement, yet today I’m a hostage, I have no rights,” said Darya.

Russia’s decision to isolate the Ukrainian territory it occupies has caused severe hardship for the approximately 2 million people living under occupation. Ukrainian citizens in parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts are cut off from their relatives, reliable medical assistance and social security services.

This isn’t what Russia promised.

In December 2019, the leaders of Ukraine, Germany, France and Russia — known as the Normandy Four — met in Paris to discuss a peaceful solution to Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine.

The heads of states agreed to open three new crossing points between Ukraine’s government-controlled territory and the Russian occupied parts of Donbas.

Instead, a year after the meeting, Russia has closed all five existing crossing points. Now, to travel between Donetsk and government-controlled areas, a person must receive a special permit from the militants to be allowed to pass through the crossing point.

According to Darya, it’s practically impossible to receive that permit. She asked for one in August to attend her grandmother’s funeral and was denied. She had to watch the funeral via Skype.

“We don’t know the exact reasons behind the militants’ reasoning,” said Veronika Artemchuk, coordinator at Donbas SOS, a non-government organization that helps people living on both sides of the war.

The only way out is to use a long, expensive and illegal route through Russia, which few can afford.

COVID-19 isolation

Darya’s case is not unique. In January 2020, over 250,000 people crossed the contact line each week. In January 2021, less than 1,000 people are allowed to cross each week.

Officially, the militants keep two checkpoints open, one near occupied Luhansk and one near occupied Donetsk. The Donetsk one works two days a week, for several hours.

Only people in critical conditions are allowed to leave the occupied territories.

Everyone the Kyiv Post was able to talk to has been denied exit, despite deaths of family members, medical conditions, or the need to return home to the government-controlled territory.

The Russian-led militants systematically erased all traces of Ukraine from the region. Ukrainian television, radio and print were banned during the early stages of the war. Ukrainian-language signs were demolished. Ukrainian mobile carriers were shut down and Ukraine’s currency, the hryvnia, was substituted by the Russian ruble.

Now they are ripping families apart. The border closure cut Darya and her youngest child off from their family.

Soon after the war started in 2014, Darya’s family fled the occupied region. However, Darya and her then-husband decided to move back to Donetsk within a year. “Our house was built by my father, a miner. If I leave today, the house will get ransacked,” she said.

Part of her family stayed in the free part of Ukraine.

“My oldest son told me that he won’t return until they stop shooting,” said Darya. “They never did, so he never returned.”

Darya gave birth to her third child and stayed in Donetsk, working as a saleswoman. She often visited her two other kids, parents and grandmother in Ukraine’s western Lviv Oblast. Darya last visited them in 2019.

It all came crashing down in March. The militants have kept the border with government-controlled territories sealed since then.

No rights

In mid-March, the Ukrainian government imposed a two-week lockdown after the country recorded its first COVID-19 death. The five existing crossing points between the government-controlled territory and occupied parts of Donbas were temporarily closed.

According to Ukraine’s Border Guard Service, the checkpoints only permitted people traveling home to their place of registration. The drastic measures came out of the lack of information on the pandemic’s severity in occupied areas.

In response, Russian-led militants shut down the crossing points completely, citing the same reason. People traveling to the occupied region were forced to sleep in no man’s land in tents provided by human rights groups.

Workers of the State Emergency Service of Ukraine accommodate people stuck in no man’s land near the Novotroitske crossing point in September 2020 after the Russian-led militants denied them entry into the occupied zone. (State Emergency Service of Ukraine)

Ukraine’s quarantine was lifted in late May. However, the occupants kept the crossing points closed. Some think it’s because they wanted to keep infected people out — due to the low capacity of their laboratories and hospitals.

“There’s some logic to the decision,” says Artemchuk from Donbas SOS, meaning that they want to keep people out. “The situation with COVID-19 (in the occupied Donbas) isn’t good, people can’t get a test, they can’t buy proper medication.”

However, the militants didn’t close anything else — there were never any quarantine restrictions in the occupied territories.

“Bars are open, clubs are open, the border with Russia is open, the only thing closed is the crossing points into Ukraine,” said Darya.

“Everyone knows (the militants) are just making money on it,” she added, meaning that people have to pay the local carriers who take them through Russia.

Darya’s latest attempt to get out of Donetsk was in October when her father was hospitalized with COVID-19. Darya said she was once again denied the right to exit.

The illegal route

Unable to get to Ukraine through checkpoints, some choose to go through a much longer and illegal way — through Russia.

The Russian-led militants don’t guard the border with Russia, making it the only way to flee the occupied territory. It’s illegal.

Iryna, who lives in Donetsk, was one of the people who took the long way into government-controlled territory. She had to travel over 1,700 kilometers to get from Donetsk to Kharkiv through Russia so her daughter could get a higher education. Before the war, a trip between Donetsk and Kharkiv was 300 kilometers and less than four hours.

Iryna and her husband used to live in the U. S. In 2011, they returned to their hometown of Donetsk to open a business. When the war began, Iryna gave birth to her second child. Soon their business was ransacked, leaving the family without money to leave the region.

Iryna said that the militants kept her husband in a cell for two months because of his U.S. passport, which they found suspicious.

In 2020, Iryna’s older daughter finished high school in Donetsk and the family decided that it would be better for her to continue education in Kharkiv. The crossing points were closed, forcing the family to travel by car through Russia. Iryna said it was a tough experience, which she’s not ready to repeat. She is now back in Donetsk.

She says there are local carriers who offer to take travelers from Donetsk to government-controlled territory, through Russia, for $120 one way. For locals in Donetsk, it’s a lot of money.

The militants “are simply doing business on travelers,” she adds, echoing Darya’s words.

(Ministry of Defence / Kyiv Post)

People without money or a car can’t make the trip. According to Artemchuk, before the shutdown, locals used to cross into the free territories frequently to get qualified medical assistance or social services including pensions, visit family and work.

Darya, who lives only five kilometers from the government-controlled territory, said she can’t afford to travel thousands of kilometers through Russia.

The trip would be illegal. Ukraine doesn’t permit crossing the country’s border bypassing official crossing points. The Border Guard Service is required to fine violators for Hr 1,700 ($80). But Iryna said she wasn’t fined.

According to people who take the long route, Ukraine’s Border Guard Service tends to overlook the infraction. People have often succeeded at appealing their fines in court, citing the right to freedom of movement.

The Border Guard Service declined to comment on the issue.

Since recently, those traveling from the occupied territories through Russia run into another complication. In January, Ukraine’s Health Ministry marked Russia as the COVID-19 “red zone” country, meaning that people coming from Russia have to self-isolate for two weeks.

Russian sabotage

The situation in Donbas goes directly against agreements reached in Paris. Over the past seven years, Russia has actively sabotaged peace negotiations, prolonging the war and exporting misery.

Ukraine has fulfilled all requirements for a new Normandy Four meeting to take place, said Ann Linde, chair of the Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe (OSCE).

“At the Paris summit, there was an agreement on a new meeting of leaders under several conditions,” said Linde in a recent interview with a Ukrainian news outlet. “Ukraine has fulfilled all conditions, Russia, unfortunately, hasn’t yet.”

President Volodymyr Zelensky (L), French President Emmanuel Macron (C) and Russian President Vladimir Putin attend a Normandy Four meeting at the Elysee Palace in Paris on Dec. 9, 2019. (AFP)

These conditions include willingness to swap all prisoners, disengage armed forces in three designated areas and build three new crossing points.

President Volodymyr Zelensky, who was elected on a promise to end the war, went to great lengths to try to do so. In September 2019, Russia and Ukraine swapped prisoners for the first time in three years. Two more exchanges followed.

In 2020, Ukraine agreed to withdraw troops from three more points, after already having withdrawn troops from three locations in 2019.

Ukraine has also completed the construction of two new crossing points, which are equipped with social services offices, Ukrainian banks, coronavirus testing stations and washrooms.

Russia-led militants have done none of that.

In late-April, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov told the press that he doesn’t see the point in holding another Normandy Four meeting. Russia’s position hasn’t changed since then.

On Jan. 12, Zelensky’s chief of staff Andriy Yermak met with Russian representative Dmytro Kozak in Berlin. Mediators from Germany and France were also present, with the meeting being labeled as the Normandy Four advisory meeting.

After the meeting, Kozak told the Russian state media that “solutions to almost no issue have been found.”

Since the Kremlin launched its war nearly seven years ago, Russia has actively tried to give Russian-controlled militants official status in the peace negotiations and label Russia’s war against Ukraine as a civil war.

With negotiations stalled, about 2 million people are kept hostage in eastern Donbas and are not allowed to leave.

“There’s nowhere to run,” said Iryna. “No one is waiting for us.”