In Ukraine’s Donbas, coronavirus is pushing people on both sides ever further apart

The war in Ukraine is now in its sixth year. Coronavirus has shut down the frontline crossing points that thousands of people use every day to get home, visit relatives and live their lives.

Overnight on 14 May, soldiers at the Novotroitske crossing in Donbas heard a mine explode. The next morning, a woman crawled over to the Ukrainian position - her foot had been blown off by a Russian anti-infantry mine. As reported by Ukrainian soldiers, the woman was well-dressed and talked in detail about how she had travelled to Moscow for a training course, how she wound up in Donetsk - and why she needed to go home to Avdiivka, some 60km north. She also told them which documents could be found in her bag. The only thing the woman couldn’t do was explain why she had decided to walk out into a minefield from Dokuchayevsk - a town on the wrong side of Donetsk if you want to go to Avdiivka. Her bag, as it turned out, was empty.

Due to the COVID-19 epidemic, both sides in the conflict - Ukrainian and pro-Russian - have closed the crossing points in Donbas. Previously, thousands of people would cross the frontline on a daily basis, but now this has come to an end. This has made local life significantly more difficult, affecting the economy of the frontline territories. Since war broke out in 2014, a network of businesses and infrastructure has emerged to serve the stream of people and vehicles crossing the line of contact. There were five crossing points between the two sides, and each one had its own recent history, logistics and corruption. Now these crossings are being negotiated over.

Official permission for people to travel to the “Donetsk People’s Republic” (“DNR) and back was renewed on 22 and 25 June, but the way the crossings have been organised raises many questions. An electronic system of registration, the application procedure for entry, the mandatory quarantine in “DNR” hospitals and other innovations significantly limit the number of people who can travel. This has forced them to take extreme measures, including sleeping at checkpoints.

At the same time, the border between the self-proclaimed “republics” and Russia is already open, and residents of “DNR” and “Luhansk People’s Republic” (“LNR”) with Russian passports are travelling - some of their own volition, others in organised groups - to vote for amendments to the Russian constitution.

End of the line

“Las Volnovakha doesn’t exist anymore,” Yulia says sadly as she guides me around the town, the “Las Vegas” of this side of Donbas. “Look around,” she says, “there’s so many less people.”

Volnovakha, a town to the south of the Novotroitske checkpoint, has swiftly turned into a logistics centre as the war has continued - perhaps the biggest in Donbas. Nefore the coronavirus outbreak, six trains would pull in here every day - from Kyiv, Kharkiv, Lviv and Odesa - and as soon as they arrived, they would be swarmed by transport agents. Over and over again, pensioners and displaced persons from Donetsk would visit the local market in Volnovakha, the supermarket, the pension office, the state savings bank and numerous phamarcies - to take back everything they needed to Donetsk.

The war in Donbas has affected two regions of Ukraine and 400 kilometres of frontline. But if you look closer you can see that there’s no single line of trenches here, and streams of people cross the contact line every month - whether the 900,000 crossings a month in February 2020 or 1.5 million in August 2019.

These figures don’t support Russia’s narrative of a “civil war in Ukraine”, and the authorities in the “republics” have tried to stop the crossings. For instance, all public sector workers in Donetsk and Luhansk have to sign statements to the effect that they “will not visit Ukraine”. Parents of police cadets and relatives of military personnel have to give similar written statements. There was an attempt to restrict crossings more simply, too: in recent years, the long queues have been only from the side of the self-proclaimed republics.

But now, Volnovakha’s pension office is empty - and for three months, the town has been learning how to live without supporting tens of thousands of people traveling to Donetsk and back.

“They bought food first and foremost. You couldn’t get into the supermarket when the Donetsk people came through,” tells me Evgeniya Reutskaya, who sells home goods at the market. “They would buy lightbulbs, CDs, plastic basins and buckets. Now the numbers are down by 50%. A third of that is people from Donetsk, and the others are people who haven’t made it in from local villages due to the transport freeze. But most of the money was made in the town centre: people would line up to the pension office or state bank and then run round the shops - chemists, sausage, bread and water.”

Pensioners from the self-proclaimed “republics” can only receive their pensions if they are registered as displaced persons to a specific address. In Volnovakha you can see flyers for registering people everywhere. Online, for example, you can encounter comments referring to people from the “republics” in derogatory terms: “Now these locusts will come again!”

Raised uncertainty

To understand what’s happening on the line of contact since the start of the epidemic, you need to understand the Minsk process - the peace process for eastern Ukraine. Political and economic life in the “uncontrolled territories” interweave with the epidemic rather bizarrely, especially given the differences between them.

The top posts in Donetsk and Luhansk are occupied by people with very different backgrounds. In Luhansk, you have a Ukrainian security official, Leonid Pasechnik. Whereas in Donetsk, you have a former pyramid scheme manager, Denis Pushilin. The “republics” differ by territory, population numbers and industrial potential. Luhansk is more densely populated and, as many consider in Donetsk, better managed.

Donetsk makes announcements about integrating with Russia more often, but there’s more people with Russian passports in the “LNR” (120,000) than the “DNR” (92,000). Getting a Russian passport is a centralised process: the majority of people are public sector workers, state enterprise managers and local military personnel - and all go through their human resources departments.

But when the “curators” from Moscow interfere in management, the “republics” act in tandem, as a rule. In both territories, the word “quarantine” only applies to schools. The fight against the epidemic began within the framework of a “regime of heightened readiness”, announced in March. That’s when “offices” to prevent infection were opened. All “non-quarantine” events were introduced in both “republics” against the backdrop of an ongoing state of war and curfew between 11pm and five am.

Those who make decisions about the “republics” are having to find a balance between dealing with coronavirus, harming the barely breathing economy and urgent matters on the public political integration with Russia

Still, there has been a difference in managing the epidemic. In Luhansk, restrictions were put on bus travel between population centres, and public transport was ended in Bryanka, Alchevsk, Pervomaisk and Perevalsk. Between 8 and 16 June, “anti-coronavirus” military blockades were set up in Rovenki, Sverdlovsk and the whole of Antratsit. In a video message, the head epidemiologist of “LNR” told people to stay at home and wear masks when going outside. The authorities also shut down mobile internet, and in certain districts - the internet completely.

Meanwhile, on 5 June, miners at the Komsomolskaya coal mine started an underground strike, which was due to be supported by three other mines in Luhansk. It’s impossible to subdue a protest in a gas-filled mine works by force, so the authorities chose other methods. The three other mines were closed, and the strike-ready replacement shifts were not permitted to go underground. Army units surrounded the potentially explosive territories on the pretext of preventing the spread of coronavirus, and 42 striking miners were arrested by state security.

The “DNR”, on the other hand, did not close any towns off, or shut down transport due to local outbreaks of coronavirus. But while markets, enterprises and shopping centres remained open, theatres, cinemas and resorts were closed. In short: public transport was working, but pensioners were no longer allowed to travel for free; all factories were working, but gyms were closed; large sporting events were banned, but the Victory Parade on 24 June went ahead with the maximum number of people.

Viral politics

Those who make decisions about the “republics” are having to find a balance between dealing with coronavirus, harming the barely breathing economy and urgent matters on the public political integration with Russia.

Between March and 22 June, the “republics” did not permit the OSCE monitoring mission nor representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to enter on the pretext of preventing COVID-19. Prisoner exchanges came to a halt after IRCC representatives were not able to visit detention sites in the “republics”, as agreed in the Normandy format talks in Paris.

There is, of course, an epidemic in Ukraine’s uncontrolled territories. In May, for example, the head doctor of the main coronavirus hospital in “LNR” died. In Donetsk, one hospital after another was closed for quarantine. In May, nearly all planned operations were stopped, and ICU, pulmnology and other wards were closed at several large hospitals. And while a 250-bed mobile infection hospital was brought from Russia, it was not deployed: the existing system of infection wards and ICU coped with coronavirus patients.

Related story

Against this background, on 5 June “LNR” stopped publishing official statistics on the number of infections - the number has frozen at 429 people. In “DNR”, by 23 June, there were officially 1,029 cases of infection, with the rate rising to 35-37 people being infected a day. These numbers are used as an argument as to why it’s impossible to open the crossing points.

From 17 June, hotlines for people wanting to participate in the constitutional referendum in Russia by voting in neighbouring Rostov region were set up. There’s roughly 210,000 new owners of Russian passports in the “republics”, and they have been organised into voting parties between 25 June and 1 July. Special polling stations will be set up in 12 towns and settlements in the Rostov region.

The fight for the crossing points

On 10 June, Ukrainian forces opened the crossing at Maryinka, where a highway leads to Zaporizhzhya, but when people got to the “DNR” side, they found the crossing closed. Then, the Donetsk “authorities” announced that they would open the crossing at Elenovka for travel out of Donetsk, although the relevant Ukrainian crossing point was closed. For people coming in, they said, the “DNR” crossing would open on 25 June for people who had registered beforehand.

The decision to open and close the crossings in Donbas rests with the Ukrainian Army’s Combined Forced Operation. It reacted almost instantly overnight on 22 June, opening the Novotroitske crossing - and, in contrast to its opponent, opened it fully, for both entry and exit.

On the very first day the crossing opened, I met four pensioners there who had travelled with the hope of reaching Donetsk. They’d spent the last three months far away from Donbas - sisters Elena and Galina in Vinnitsa, and Nikolay in a small village in Volyn, in western Ukraine. The “authorities” in Donetsk had stated the day before that they would only permit entry from 25 June, and only after a complicated electronic registration process (“DNR” websites are blocked in Ukraine, and pensioners don’t use the internet).

Complete with heavy bags, four pensioners, one of them using crutches, made their way through inspections on the Ukrainian side, got to the end of the line of Ukrainian checkpoints and, not finding the usual buses on the other side, walked eight kilometres on foot. They then waited until evening at the Elenovka checkpoint, before they were sent back by the “DNR”.

At the time of writing, ten people were spending the night at the checkpoint, sitting under a small shelter at the “zero point” - the first Ukrainian checkpoint. They were all waiting for the “DNR” checkpoint to open on the other side. By 24 June, according to the Ukrainian emergencies ministry, there were more than 40 people waiting. The next day, 150 people made their way to the “DNR” side, and the Ukrainian side organised army tents for these people to camp out in.

Speaking to me, one person at the checkpoint told me that “Ukrainian soldiers are sharing their porridge, bread and water with us”. People who cross try to observe “political correctness”, and don’t use the word “our people” to either side. On the “DNR” side, it was announced that the pensioners had “participated in a provocation by Ukrainian security services”, and that they should expect to be questioned.

Phantom opening

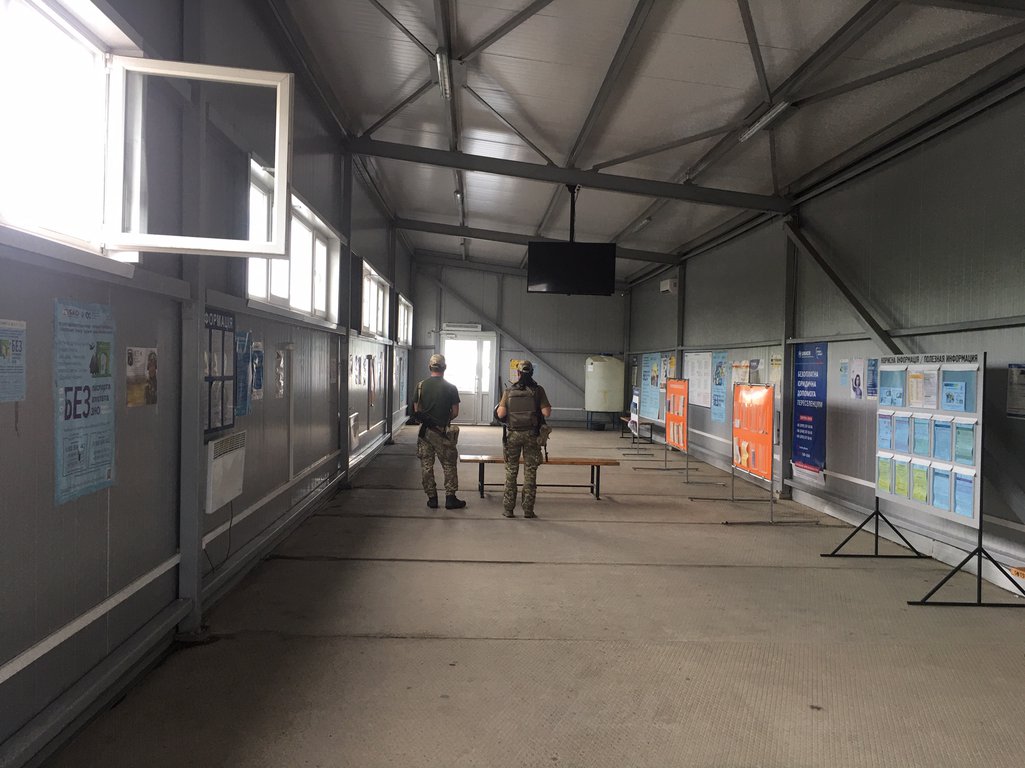

In the first days of the checkpoint working, I saw all the typical elements of reality here: no more than 150 people can try to cross into the “republic” in a single day; a whole system of checkpoints has been set up to “prevent” queues; only a few people are actually allowed up to the entry/exit point itself; crossing the entry/exit point is accompanied by the authorities photographing you, taking fingerprints; and if you have a car, then you have to store your “DNR” license plate with a paid service.

If your car has not been licensed in the “republic”, then it can’t leave for territory controlled by Ukraine. During pre-crossing inspection, everyone has to sign a paper saying that they will not return to “DNR” until the end of the pandemic. At one of the entry/exit points, newly built in August, it takes 30 minutes for someone to pass the inspection. People queuing spend the night in a local school as they wait, but more often than not they don’t make it across.

Since the start of the epidemic, the “border” between the “DNR” and “LNR” has been closed off, and it was forbidden to cross the contact line in Donetsk region. School children, cancer patients and other people from Donetsk and Makeevka found themselves in a difficult bind. The majority of them still can’t leave now.

“My wife and I travelled to Donetsk before 16 March, when it seemed that the frontline had only been closed for people from Donetsk. One of us is registered in Ukrainian-controlled territory in Donetsk region, and so we hoped to get through,” says Vitaly Omelchenko, a lawyer stuck in Donetsk. “But they closed the crossing for three months. We tried everything, we thought we could get through a ‘window’ in the frontline, but while my wife was worrying about whether she could trust the people who would take us and go past the mine fields, the window closed. Thankfully, there’s no cancer patients among us, no little kids on the other side, or other urgent circumstances, but we want to go home.”

“Windows” are unofficial corridors which sometimes give people the opportunity to cross the contact line. But hundreds of people are trying to leave Donetsk - and don’t have the right connections - just because they need to.

The most active of them have set up a Telegram group (“Forgotten in DNR, destination Ukraine”), which already has more than a 1,000 subscribers. Many want to leave Donetsk any way possible. One of the group’s moderators, a resident of a Ukrainian town outside Donbas, was looking for a way of getting her mother, trapped in Donetsk, out of the city. By June, she’d managed to do it - an informal service for crossing the Russian border had been set up (a Ukrainian passport holder can legally return to Ukraine from Russia). For 10,000 roubles, a driver in Donetsk will apply for documents to cross into Russia and guarantee the crossing into Rostov region.

Conversely, there’s a no less active group on Telegram (“It’s time to go home!!!”) trying to get back to Donetsk.

People who want to cross the border look for various ways of doing it: they send an avalanche of emails both to the “DNR”, as well as all kinds of international organisations, local rights defenders and Ukraine’s ministry on reintegration of temporarily occupied territories. For example, the “Forgotten in DNR” group sent a list of 50 people particularly in need of crossing the border to the humanitarian subgroup of the Minsk process.

Two sources, a moderator of the “Forgotten in DNR” group and another, close to the military in Mariupol, told me about attempts at provocations while the checkpoints have been closed. At the start of May, for example, a number of bots entered the Telegram group and proposed that participants form a crowd and try to storm the Ukrainian entry/exit point, promising loyalty and entry into “DNR”.

“We followed this activity very closely and saw the risk as real,” says Mariya Podybailo, who teaches information security at Mariupol State University. “We were afraid that there’d be an agent provocateur in the crowd who could, for example, throw an explosive at our first checkpoint. I know that when the charge was expected, local army and marine units were mobilised at the Novotroitske crossing on 13 May.”

No one attempted to rush the crossing point in the end, but others, it seems, decided to try and make their way through the minefields - as shown by the case of the woman injured on 14 May.

When you write about Donbas, sometimes you’re seized with helplessness. For example, it’s impossible to explain why people stay living in houses that come under artillery fire, or why they refuse to be evacuated, as happened in Debaltseve or the village of Opytnyi, or why people still live in Vodyanoe near Mariupol. The desire to live at home ranks above even the basic need of safety.

In the Telegram groups “Forgotten in DNR” and “Time to go home!!!” you can see people writing desperate messages in real time - people who couldn’t stand the heat waiting in the queue to cross the line of contact or are in the “grey zone” between the Ukrainian checkpoints and “DNR” checkpoints. Since 22 June, the Elenovka crossing is not letting more than 200 people cross a day.

These crossings in Donbas have clearly turned into a object of political negotiations, and while the Covid-19 epidemic continues you can say with confidence that these crossings will not be opened fully any time soon.

The end to “mass transit” over the contact line will work towards the mental divide between residents of a region brutally divided by a frontline. Both sides understand this. The fight for the crossing points, rather than the fight against Covid-19, will become the main trend of the conflict in Donbas this summer.

If you value our journalism, please support us

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.